James Beaney was a surgeon at the Melbourne Hospital from 1860 to 1891. His every step invited controversy and divided public opinion.

Key points

- James Beaney was a surgeon at the Melbourne Hospital from 1860-91

- He was known for his medical boldness, self-promotion and lavish lifestyle

- He also invited controversy and divided public opinion and clashed with the medical profession and law

- His legacy remains about Melbourne today

James Beaney was a surgeon at the Melbourne Hospital from 1860-91. Known for his medical boldness and notorious for his self-promotion and lavish lifestyle, his every step invited controversy and divided public opinion.

The conduct of a surgeon who drank and served champagne to guests he invited to watch as he performed operations with hands adorned with jewellery is something that would be condemned today as outrageous and unacceptable. But from 1860 that was the common practice of Melbourne surgeon James George Beaney – a practice that was to earn him the dubious nickname "Diamond Jim" and guarantee him a place in the city's history as one of its more controversial and colourful celebrities, loved and despised in almost equal measure.

This is an online version of a display at the RMH in 2011.

Who was James George Beaney?

Doctor, Politician and Philanthropist. Honorary Surgeon to the Melbourne Hospital 1860-65 and 1875-91

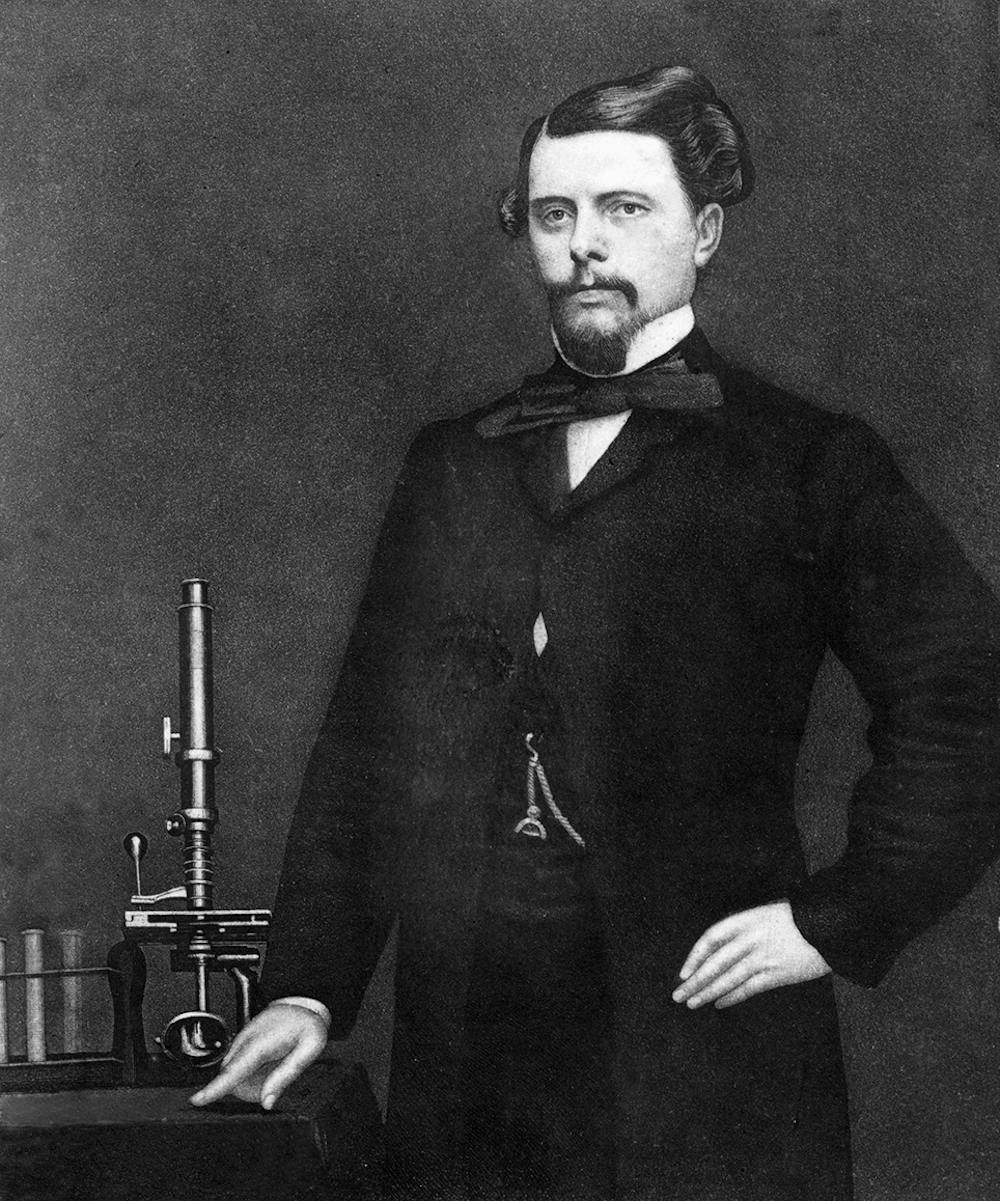

James Beaney was a surgeon at the Melbourne Hospital from the 1860s to the 1890s. A flamboyant character given to lavish entertainment of his students and followers, he was nicknamed "Diamond Jim" for his clothes decorated with diamond studs, bejewelled gold watch with diamond and ruby rings on his fingers, and "Champagne Jimmy" for his love of champagne.

He was notorious for his self-promotion, for his lavish bequests and gifts, the publication of a stream of medical texts, and the opulent style in which he lived and practised surgery. Contemporary observers indicate that he was a bold surgeon, perhaps rash and rough at times, yet often successful when others less daring would have failed.

This boldness, however, led to conflicts with the Medical Society of Victoria. A controversial figure, Beaney faced several libel actions, and in 1866, a trial for murder. Beaney was one of the most notorious doctors in 19th-century Melbourne.

Born in Canterbury, England on 15 January 1828 to working-class parents, he commenced a surgical apprenticeship and then studied in Edinburgh. Ill-health, most likely tuberculosis, led him to travel to Melbourne in 1852. After working in a pharmacy in Collins Street, he returned to Edinburgh in 1853 and qualified as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1855.

This was followed by a period of military service as an assistant surgeon to the 3rd Regiment of Scots Guards in Gibraltar, and as a staff surgeon in Turkey during the Crimean War. After returning to England he studied venereology in Paris and visited America as a surgeon in emigrant ships before arriving back in Melbourne in 1857.

Beaney rapidly established himself as a prominent surgeon. He was first appointed an Honorary Surgeon to the Melbourne Hospital in 1860, and apart from the period 1865-75, continued in this position until his death in 1891.

He continued his military association as a surgeon in the Royal Victorian Artillery and as a foundation member and early benefactor of the Pipeclay Club, a forerunner of the Naval and Military Club. Beaney was also a member of the Medical Society of Victoria, Royal Society of Victoria, the Royal Irish Academy and the Melbourne Yorick Club and a member of the Senate of the University of Melbourne.

He was elected a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh in 1860, was admitted to the degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Melbourne in 1879, and Doctor of Medicine at St Andrews University, Scotland. He was also made a Licentiate of the King and Queen's College of Physicians in Ireland in 1879. Beaney married Mary Susannah in 1870, but she died in 1879. They had no children and he never remarried. He died on 30 June 1891.

Beaney’s gravesite in the Melbourne General Cemetery is marked by a large monument and towers over its neighbours. The grave is located in Church of England, Section K, grave number 263.

Beaney was a colourful character and was described as a "short, podgy man with pale blue, rather shifty eyes, with his hair swept up to either side of this head like a pair of horns". His flamboyant dressing of frock coats embellished with velvet collars, diamond shirt and cuff studs, diamond and ruby rings, a bejewelled gold fob watch and chain and diamond pendant, made him a subject of caricature and earned his the nickname "Diamond Jim".

Many incidents bear witness to his vanity and egoism. He would invite his friends to watch him operate wearing his diamond rings, and he travelled in an open carriage pulled by two horses and filled with the most expensive rugs.

It is reported that Beaney earned over £12,000 a year, an extraordinary sum in those days. His considerable fortune had been won by exuberant self-advertisement of everything that he did. With his successful career and material success he was able to parade as a leading member of the community. He revelled in personal success and adulation whether in honours or positions he held in a club or Parliament. He rewarded his supporters with lavish banquets and gifts.

A lover of claret and champagne Beaney advocated alcohol, especially champagne, for most disorders. He always liked a bottle of claret for breakfast and a small bottle of champagne for lunch, then again at dinner. He believed in prescribing alcohol for most illness, although admittedly at a time when this was not unusual. Beaney saw 63 patients at the Melbourne Hospital during August 1883, prescribing 122 ounces of brandy, 101 bottles of ale or porter, 14 bottles of lemonade and soda water, and two bottles of champagne.

He was known to extend hospitality to his medical students after operations, serving champagne during and after surgery and gave his surgical pupils gold and silver medals after competitive examinations.

"During my second year I joined a large concourse of students in the old operating theatre of the hospital, where Beaney was about to perform an operation… namely to tie the abdominal aorta for aneurysm. From my position well at the back of the gallery I got glimpse of the busy little man in the frock coat. I saw him again on the following day with his house surgeon leading a procession of students to the Mortuary to inspect the result of his operation."

After unsuccessfully contesting an election for the Melbourne Province in 1882, Beaney was elected to the Victorian Legislative Council for the North Yarra Province from March 1883 to June 1891. His most important political action was in 1886 to establish a Select Committee, with himself as Chairman, to inquire into the sanitary condition, construction and possible removal of the Melbourne Hospital from its then location on the corner of Lonsdale and Swanston Streets.

Public concern over deaths at the hospital had been aroused by articles in the press and by criticisms voiced by the city coroner, Dr Richard Youl. The Committee’s report vindicated the hospital in most respects, attributing the high mortality to the admission of dying patients rather than to infection acquired in the wards as alleged by Youl.

The suggestion that the hospital should be built on a new site close to the University of Melbourne - a recurring theme for over half a century until finally achieved in the 1940s - was rejected. However in the face of public criticism that Beaney had unduly influenced the Committee, and because the Legislative Council disagreed on the conclusions and the evidence leading to them, the Committee’s report was not formally adopted.

Beaney’s house at 133-139 Collins Street is listed by the National Trust on the Victorian Heritage Register for its local significance.

In 1887, Beaney held a competition for the design of a new house and surgery in central Melbourne. The resulting lavish mansion, originally three-storeys, on the corner of Russell and Collins Streets remains impressive, even when dwarfed by adjacent high-rise buildings. The house in 1916 became the Alexandra Club, a private women’s club, and was later used as a bank and a luxury shop.

"One event I should not forget, the dinner given by Dr J.G. Beaney in his own house which he built at the corner of Collins and Russell Streets…. It was given to his dressers in their third and fourth years, I happened to be included. It was a wonderful champagne dinner, no skimping either of food or liquor, and with the height of hospitality, beds were provided for any of the guests who did not wish or were not able to go home. Quite a number accepted this hospitality."

Dr Frank E. Littlewood: A Memorable Year: Recollections of a Medical Student, 1887-92

The medical profession and Beaney

Conflict and bitter in-fighting characterised the medical profession in Victoria in the second half of the 19th century. While there was sometimes a clear division between the old guard and the new, more commonly differences were not based on clear ideological lines but more on factions, personality differences and friendship alliances.

Beaney, who had come from a working-class background, had a successful medical practice making him one of the wealthiest doctors in 19th-century Melbourne. However the flamboyant Beaney, with his crass nouveau riche (someone who has recently acquired wealth) manner, was not a gentleman by conventional standards of the time and his very lifestyle irritated much of the medical establishment.

He showed little respect for ethical standards and engaged in self-promotional advertising, buying votes for hospital elections, and getting others to write his books and speeches. However he was also willing to lecture to students and encourage medical education and he published extensively, albeit at times for questionable motives. This was not always the case with his medical contemporaries.

Beaney was a member of the Medical Society of Victoria for a decade before his resignation in 1870. Several factors forced his resignation from the society including a charge of murder in 1866 where his medical enemies took the stand against him, and the labelling of his popular books on contraception, family planning and sexuality in conservative Melbourne "as that class of literature which honourable medical men shun". In addition, much of the medical profession opposed Beaney because of his self-promoting flamboyance and egotism.

Beaney’s conflicts with the Medical Society of Victoria reached a peak in 1878-79 when he visited Britain bearing a letter of introduction from the Premier Graham Berry. He was welcomed - with the presumed authority from the Victorian Chief Secretary - as the representative of the medical profession in Victoria. This claim was vehemently denied in two printed circulars sent by the Medical Society of Victoria to all leading medical organisations in the United Kingdom.

Evaluation of Beaney’s contribution to surgery is difficult. His claim to surgical originality probably cannot be substantiated, but he appears to have been informed on the then current practices. However, to the end of his life he failed to appreciate fully the antiseptic principles of Lister. He operated in an old blood-soaked coat, his fingers encrusted with his favourite diamond rings. Unlike some of his colleagues, however, he did not attend autopsies on the same day as he operated.

Beaney was a competent surgeon by the standards of the time. The evidence of contemporary observers indicate he was a bold surgeon but without the finesse and skill of a top surgeon. While rash and rough at times, he was often successful when others who were less daring would have failed. He twice operated successfully for aneurysm of the innominate artery (which brings blood to your right arm, head, and neck), a hazardous procedure in which few surgeons were successful. He also had the courage to operate, although unsuccessfully, to ligate the abdominal aorta. In contrast, in four inquests on patients dying after surgical procedures, he was placed in the position of having to defend himself against charges of incompetence.

With his training from the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh Beaney must have been a competent surgeon, however his detractors argue that "even this examination became notoriously lax with the shortage of surgeons during the Crimean War" when he graduated.

Hospital surgeons were required to give clinical lectures to medical students, often at a patient's bedside. Beaney gave his with much flair, and usually had one lecture a year published and widely distributed. His lecture was usually followed by free champagne. He also issued gold and silver medals to those students who received top marks in operative surgery. These medals were highly sought after by the students for they were virtually the only distinction available to them apart from the honour prizes and exhibitions awarded by the university.

Beaney's Ward Books detailing his treatment of individual patients can be found in the Public Record Office Victoria (Series VPRS 12477). Ward books are a record of the symptoms, medical observations and treatment of patients under the care of the hospital's honorary medical consultants such as Beaney. However, the actual entries were often written by the more junior resident medical doctors under the supervision of the consultant.

The law versus Beaney

Beaney suffered a series of embarrassing court cases, including a charge of murder. He was placed in the position of having to defend himself against charges of incompetence in four inquests on patients dying after surgical procedures.

Mary Lewis

The first inquest led to Beaney’s trial for murder of a 21-year-old barmaid, mother-of-two Mary Lewis. On 12 March 1866, Mary Lewis at the Terminus Hotel, St Kilda consulted Beaney, having already consulted two other doctors, one of whom thought she was pregnant. Beaney visited her in her lodgings three times, and on the last occasion, administered chloroform "to give her a sleep". Mary Lewis died the following day with what would appear to be an established pelvic infection although on her death certificate Beaney said the cause was "a malignant disease of the uterus".

Due to rumours of an illegal abortion, the Coroner ordered a postmortem, and despite an inconclusive finding, Beaney was charged with murder. During the first trial, the jury failed to agree, although it was rumoured that he was within one jury vote of being hanged.

At a second trial Beaney was acquitted after his lawyer called no witnesses for the defence but relied on his cross-examination of expert witnesses to disagree on almost every aspect of the medical evidence.

Robert Berth

Robert Berth was a patient admitted to the Melbourne Hospital on 26 November 1875 suffering from a stone in the bladder. Four days after his admission he was operated on by Beaney. At that time there was a hospital rule that no important operation should be performed without prior consultation with other members of the surgical staff except for emergencies. Beaney disregarded this rule.

During surgery, it was discovered that the stone was much larger than originally estimated. As Beaney had only made a small incision, the stone could only be removed by forcing it through the incision causing the surgical instruments to bend and resulting in inflammation of the bladder and peritonitis. Robert Berth was not under anaesthetic and died.

A few days later the stone was exhibited in the window of a bookseller in Collins Street with a printed card stating "This stone was removed from a patient’s bladder at the Melbourne Hospital by Dr. James G. Beaney". The flagrant exhibition of this stone incited Beaney’s professional enemies. A fortnight after the operation a letter appeared in The Argus newspaper suggesting that Beaney’s surgical skill was open to question and drawing attention to his disregard of the hospital rule regarding consultation. This letter was brought to the attention of the Minister of Justice, who ordered the police to enquire into the affair.

An exhumation of the body was ordered and a postmortem performed. This was followed by a Coroner’s inquest with a jury to determine the cause of Berth’s death, with Beaney facing charges of culpable negligence. Beaney engaged an eminent Queen’s Counsel to act on his behalf, and he in turn so confused the jury with the medical evidence that the majority were unable to agree as to the cause of death. Beaney was acquitted, although he was criticised for failing to adhere to the Melbourne Hospital’s rule that consultation with other honorary surgeons must precede a major operation.

Beaney was a public figure who polarised people. While he was despised by some members of the Melbourne medical and social fraternity of the time, others were enchanted by him. Only three weeks after the inquest into Robert Berth's death, a lavish dinner was given in his honour presided by the Lord Mayor, and Beaney was presented with a silver inkstand by his friends and patients as a token of their esteem. Beaney, seeing the commercial potential of the trial, published Doctors Differ, a book which portrayed the bitter infighting of doctors and which discredited the professional capabilities of his fellow practitioners.

Beaney and the media

"Diamond Jim" Beaney was probably the most scandalous doctor in late 19th-century Victoria.

The Medical Society of Victoria condemned him as a bogus practitioner and the daily press published details of his unsuccessful operations.

His visible crassness, physical characteristics and ostentatious lifestyle led to him being repeatedly caricatured in the press.

Beaney the author

Beaney’s numerous publications began in 1859 with Original Contributions to the Practice of Conservative Surgery. This was the first book devoted to surgery to be published in Victoria, and one of the first medical books published in Australia. The book met with a mixed local reaction and Beaney was accused by one reviewer of using the book to advertise his skills as a surgeon to the public.

Over the next 25 years, this book was followed by numerous other works dealing with disorders of sexual and genitourinary function, the history of surgery, joint disease, vaccination, childhood ailments and clinical lectures given to medical students.

Almost 30 papers in various local medical journals appeared under his name, the most notable a series on anaesthesia. However, Beaney’s works were not without criticism or controversy, including an editorial article in the Melbourne Medical Record in May 1875 entitled ‘A great author who plagarises (sic) other men’s works’, which described one of his books on syphilis as a paraphrase of a translation of a German work.

Beaney’s publisher F.F. Bailliere in 1880 presented him with a bill of £400 for the sale of his medical textbooks and for Bailliere’s role as an "agent for the procurement of a Letter of Introduction for Beaney to senior officials and doctors in Great Britain and Ireland". Beaney refused to pay and an acrimonious court case followed, which he won. During the court case, it was revealed that some of his works had been ghost written. How many of the actual books published under Beaney’s name were in fact written by him is difficult to know.

For a complete list of Beaney's published works see: Bryan Gandevia: "Some aspects of the life and work of James George Beaney" in The Medical Journal of Australia, 2 May 1953, p 14-19

Beaney's legacy

Beaney’s will, although later criticised as not providing adequately enough for his surviving relatives, reflects his generosity to charitable and educational causes as well as his vanity.

He was the first benefactor to the University of Melbourne’s Medical School with £2000 left in his will to establish scholarships in surgery and pathology. These were the first bequests received by the University’s Medical School. He also donated £1000 to Guy’s Hospital in London for a scholarship in Materia Medica and £1000 to St Thomas’s Hospital, London for another scholarship in surgery.

In addition, he bequeathed £10,000 to the city of his birth, Canterbury in England, to establish The Beaney Institute for the Education of the Working Man. He also left £2200 to Canterbury Cathedral on the condition that a memorial tablet in his memory, costing not less than £1200 be erected within the Cathedral. The residue of his estate of £60,000 was distributed among the University of Melbourne and seven Melbourne hospitals and charities.

The University of Melbourne’s Beaney Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology continue to this day and provide support for postgraduate research students. Combined, the annual scholarships are valued up to about $17,000.

The Beaney Memorial in Canterbury Cathedral features a relief sculpture of Beaney with a desert death scene representing the Good Samaritan and various saints. The marble memorial cost £1200

The highly ornate Tudor Revival-styled Beaney Institute for the Education of the Working Man building opened in September 1899. It was built at a cost of £15,000, partially funded by Beaney's bequest of £10,000 with the rest of the money provided by the City of Canterbury. Now officially called The Royal Museum and Art Gallery, but known locally as the Beaney Institute or simply as The Beaney, it is the central museum, library and art gallery of the City of Canterbury in Kent, England.

In 1878, Beaney donated a large stained glass window to the Melbourne Hospital. Fabricated by Messrs Ferguson and Urie at a cost of £150, the window was originally housed in the west wing of the hospital when it was located on Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. When the hospital was rebuilt on the same site in 1913, the window was relocated to the Chapel facing Russell Street.

It remained on this site after the move of the Royal Melbourne Hospital to Parkville in 1944, and the occupation of the buildings by the former Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital from 1946 to 1988.

In the late 1980s, after the closure of the Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital, the window was transferred to the Chapel of Monash Medical Centre's Clayton Campus.

Exhibition curated by Gabriele Haveaux, Archivist, The Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Thank you to the following institutions:

- Beaney Institute, Canterbury, England

- Brownless Biomedical Library, University of Melbourne

- English Heritage

- Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne

- Public Record Office Victoria

- State Library of Victoria

Sources

Ann Tovell Collection, Australian Medical Association Archive, Brownless Biomedical Library, The University of Melbourne (No. 1420, copies of Beaney photographs held at the Beaney Institute, Canterbury, England)

Beaney, J. G.: Doctors Differ, a lecture delivered at the Melbourne Athenaeum on 12 February 1876 available at the State Library of Victoria

Beaney, J.G.: Lithotomy: Its successes and its dangers, McCarron, Bird and Co., 1876 (in the Zwar Collection, No. 0013, The Royal Melbourne Hospital Archives)

"Beaney file", Alan Gregory Collection comprising background notes and papers for the writing of The Ever Open Door, The Royal Melbourne Hospital Archives

"Beaney Lane" in Melbourne: The City Past & Present

"Biographical notes re former medical staff compiled by Sir William Upjohn", No. 0124, The Royal Melbourne Hospital Archives

Chiron: Journal of the University of Melbourne Medical Society, Volume 2, Number 2, 1989

Clark, Laurel: The French Connection in 19th century Australian publishing: F.F. Bailliere and his activities

Coleman, Robert: "Bizarre - that's the diagnosis" in The Herald, 1 May 1982

Craig, C.; "The egregious Dr Beaney of the Beaney Scholarships", in The Medical Journal of Australia, 6 May 1950, p 593-8

"Dr Beaney's new residence, Collins Street" in The Builder & Contractor's News, 7 April 1888, p 222

Dunstan, Keith: "Doctor Diamonds" in The Sun, 27 April 1979, p 8

Dunstan, Keith: Ratbags, Golden Press, 1979

Gandevia, Bryan: James George Beaney (1828-1891), Australian Dictionary of Biography Online

Gandevia, Bryan: "James George Beaney: His Authorship" in The Medical Journal of Australia, 8 August 1981, p 160

Gandevia, Bryan: "Some aspects of the life and work of James George Beaney" in The Medical Journal of Australia, 2 May 1953, p 14-19

Gregory, Alan: The Ever Open Door: A history of the Royal Melbourne Hospital, 1848-1998, Hyland House, 1998.

James George Beaney, Parliament of Victoria

James George Beaney, Australian Medical Pioneers Index

Littlewood, Frank E.: A Memorable Year: Recollections of a Medical Student, 1887-92 in Alan Gregory Collection comprising background notes and papers for the writing of The Ever Open Door, The Royal Melbourne Hospital Archives (original in the Royal Australasian College of Physicians Archives)

Love, Harold: James Edward Neild, Melbourne University Press, 1989

Pensabene, T.S.: The rise of the medical practitioner in Victoria, Australian National University, 1980

UTR6.12 - The Beaney Scholarships in Surgery and in Pathology, The University of Melbourne

Russell, K.F.: "The first book on surgery to be published in Victoria" in The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery, Vol 8, No 1, July 1938, p 17-18

Russell, K.F.: The Melbourne Medical School, 1862-1962, Melbourne University Press, 1977

Smith, Julian Orm: "Stones, Diamonds, Coronets, Kings and their Surgical Custodians (address delivered to the Graduates' Society of the Royal Melbourne Hospital)" in The Archibald Watson Lecture, McLaren & Co., 1967

Sutherland, Alexander: Victoria and its Metropolis: Past and Present, McCarron, Bird & Co., 1888

Victorian Heritage Register: "Former Cromwell House", File Number B3757